Using the excuse of continuing by year of birth, I am feeling very grateful, yet heartbroken to write about my Mother’s Father, my favorite person in my entire childhood. He was born in 1920, in a village on The Hungarian Plains, south of Miskolc, and rich in his heart. While I don’t know this about my Paternal Grandparents, I do know my Maternal Grandparents grew up with religious teachings, and my Grandfather was the most influential on my spiritual development.

I may be biased, but I always believed my Grandfather was very handsome. His heart made him so, but his blue eyes and dark, wavy, rich hair also contributed. Compared with my Father on par with the height of his Father, my Mother’s Father seemed short to me, but his loving spirit seemed to make him tower over everyone.

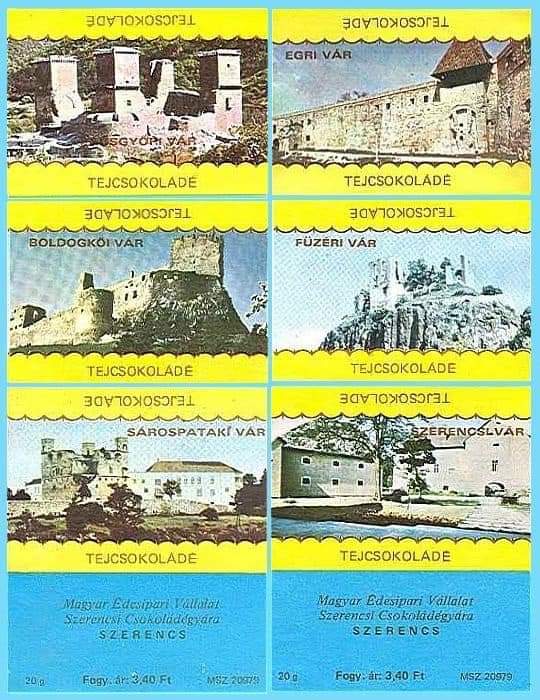

As a teen, my Grandfather was hardworking, no doubt, although I know very little about his Family. I am unsure of any Siblings. I do know as a very young man, he found himself working in the local chocolate factory, and somehow avoided WWII, despite turning twenty in 1940. As I sit here writing, I wonder if this is actually true, or was he not interested in talking about it….and I didn’t ask. As far as my Grandmother was concerned, his spokesperson most of the time, his life began in that chocolate factory where he met her and thought she was the most beautiful girl he’d ever seen. He never disputed her account of this when I was at their flat in the 1970s and 80s, he just smiled in a way that brings a sense of safety to a child.

Let’s bring in my most beautiful Grandmother then, since I seem to know equally little about her, except she was also from the Plains well South of Miskolc, born in 1924, worked in the Szerencs chocolate factory as a teen, and professed not to be interested in my Granfather at all! According to her, my Grandfather had to convince her to marry him (cue my nodding, smiling Grandfather).

Source: Facebook Group Retró ABC minden ami retró

Possibly right after WWII, the two of them married and moved to Miskolc, where work was more readily available. If there were other factors in their leaving their agricultural town with a chocolate factory within commuting distance, I don’t quite know. My Grandfather now worked at the steel plant; Miskolc was a steel town. In fact, over its decades under the umbrella of the Soviet Union, it was quite a large factory, supplying steel to all of the Eastern Bloc countries.

My Uncle was born sometime around 1946, in Miskolc. As a child, I was only allowed to see him and my Cousins there a handful of times. By the time I met him as adult myself, he was a very complex individual, and I felt I had missed out on knowing him, despite some of the oddities around his life and choices. By all accounts, he was a successful businessman and educator, with a marriage that to my eyes looked distinctly healthier than his Siblings’. Perhaps he requires his own details outside of this section, so for now, let’s go to the surprise of 1952.

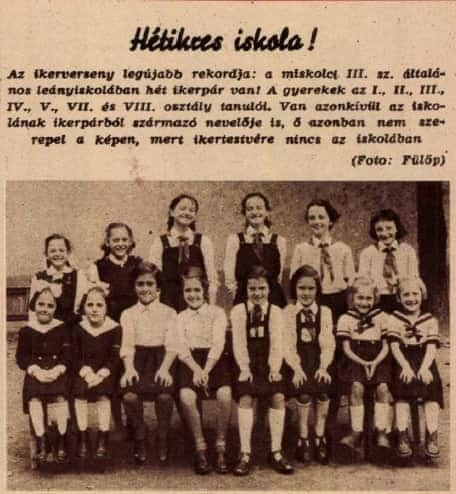

My Grandparents were thirty-two and twenty-eight, respectively, my Uncle six, when my Grandmother went into labor. She was expecting to have another month of pregnancy, but the hospital and physician were both accessible, so they were not overly concerned, until after their brand new Daughter made her debut, my Grandmother was still very much in the throes of labor. The doctor not only wasn’t surprised, he was downright expectant, I was told, and a handful of minutes thereafter, Daughter number two arrived. My Grandparents were very confused, and then panicked, as they had resources and had been planning for one, not two additional children, and now their excitement was overrun with worry. I will never forget what the doctor then told my Grandmother: “I knew you were having twins all along, and you were doing just fine. If I had told you about it, you would have just worried and complained like the other women. I no longer tell them when they are having twins unless they have a need to know.” Sit with that fury for a moment. How dare he? …but then, here are a few things to know. Culturally, Hungarians didn’t buy a bunch of items ahead of a baby’s birth, if anything, the approach was very minimalist, even for those not living on a steel worker’s income. Baby showers hadn’t been invented, nor 90% of the baby paraphernalia. Twins were a higher risk pregnancy, with stress a great factor as well, so worrying about losing the pregnancy probably wasn’t actually helpful for an expectant woman. I am not excusing nor supporting this physician’s approach, but in the 1950s, he was his own authority and wouldn’t be questioned anyway.

The next four years, with now three children had to have been very challenging for this little Family, but my Grandmother found ways to generate some income and my Grandfather earned a promotion at the steel factory, to section leader. He was now an entry-level manager, without a doubt, working hard at work and at home. My Grandmother wasn’t the shy type, and the children outnumbered them, necessitating my Grandfather’s involvement. There was one more factor in this, as well. My Grandfather was the primary source of readily available love and affection, and my Mother often described him as the go-to for understanding and empathy, even when she was in trouble. My Mother recalled her oft mischievous Sister who kept their Mother on her toes, and by following her, my Mother, in trouble. Their stunts included cutting the beautiful roses out of my Grandmother’s favorite (and probably nicest) dress.

The year 1956 arrived, the twins (my Mother and her Sister) were four years old and their Brother, ten. There was significant uncertainty in the political currents within Hungary, and a grassroots anti-communist movement was on the rise. As I wrote previously, I am not attempting to include background historical-political content best read from qualified sources; rather, I will reference certain events, then describe the impact of those on my Family. The 1956 Hungarian anti-communist movement arrived in Miskolc, as it strengthened into a full revolution against the Soviet Union. The steel workers in Miskolc joined the uprise, and as a work leader, my Grandfather then became a local leader in the anti-communist revolution. The political tides within the Westen nations supporting the anti-communist movement within Hungary changed, and those active in the uprising were almost overnight without large financial and materiel backing.

BBC News – The real life consequences of a Congress in crisis

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-67013722

This meant the Soviet Army very rapidly amd brutally beat down the 1956 Hungarian revolution, and those who were known leaders in it, no matter on how small a scale, if still alive were in immediate danger. It took a few excruciating months for my Grandfather’s turn to come, but when it did, he was taken from his Family and for the first year of his political imprisonment, my Grandmother, my Mother and her Siblings had absolutely no idea if their Husband and Father, respectively, was still alive. After a year, word came may Grandfather had been transported from a Soviet prison back to Hungary, with an accompanying twelve-year prison sentence. I can only imagine how my Grandmother felt and how much of that the twins, now five, understood. Their Brother understood a lot more, which meant he also suffered likely as gravely as my Grandmother, however differently.

My Mother remembers this period in her life while her Father, her warm, compassionate parent was in prison. She had no buffer from an extremely stressed Mother who was now facing the most severe financial and social barriers in her life. For context, I will mention, when the Soviet Army beat the Hungarian anti-communist revolution and ‘restored order’, they launched significant propaganda to deeply villainize those involved in the uprise. Their Families fared no better. They were either reeling from their loved-one’s death or imprisonment, but most had no time to grieve, as they had to move on with the realities of life and, like in the case of my Grandmother, work hard to replace my Grandfather’s income and tend to the children, also grieving, pouring from an empty cup. What was not an ideal Mother-Daughter relationship before my Grandfather became a political prisoner, was now a new battle for survival, with not a single one of them (my Grandmother and her children) receiving emotional and financial support, community empathy, understanding and tools for coping. I was told my Grandmother did all the labor a 24-hour day would allow, often relying on her Son and having no choice but to keep all four of them in survival mode.

Over the years, I heard talk of my Grandmother having some anger toward my Grandfather for not ensuring he kept out of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, but that seems like normal human emotion, at least to wish things hadn’t gone the way they did. The same talk also alleged my Grandmother did not endure the entire time as lonesome as her marital commitments may have prescribed, but I was never appreciative of that line of accusation. My Maternal Grandmother, like my Paternal Grandmother, provided a data point, now the third, for just how critical a woman’s ability to make a living was. In this regard, it seems my Paternal Grandmother, in her devastating circumstances, had a lesser load, with a more marketable skill and just one child. Time would show in my perception however, my Mother’s Mother absorbed the least of her stress, in absence of better tools in an extreme socio-economic and political situation, inadvertently loading her children with it. Living on the fringes of society, for whatever differentiating factor, takes a serious emotional toll on one’s psyche. Devastatingly, my Grandmother had no oxygen mask for anyone.

Relating today’s events to what it was like living in post-1956 Hungary can be summed up by this BBC article:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-67427422

Six years into his twelve-year sentence, my Grandfather was released for good behavior, went the Family story, but I imagine there were political and logistical factors in his release; maybe even pressure to seem humane. I have very little account of my Grandfather’s integration back into the Family and a world now six years more complex, but from other stories, I came to understand he emerged with a great sense of what contentment in life looked like, peace and love. My Grandfather accepted whatever feelings of resentment my Grandmother may have expressed, whatever ways she coped to keep herself and the children going, the fact that his children were now much more grown and shaped by the six years of survival mode, as well as his shunned place in society.

My Grandfather returned to the steel factory as a worker and remained there until he reached the standard retirement age, as determined by the Hungarian communist government. Extremely adversity, especially his year in a Soviet prison, had not turned my Grandfather bitter, it turned him even kinder. His life philosophy, his spiritual core, he often shared with me, especially when he and I would stop by at the local church for a bit of quiet time, sitting in wooden pews and staring at massive murals of dramatic scenes I seldom actually processed. We never went for the service, or in the case of this church, the Catholic mass, we went at random times, and I loved my time with him there. My Grandfather didn’t speak in terms of Bible stories or verses, and he didn’t use flowery religious words to signal a particular identity. Our conversations were unencumbered by the ungendered Hungarian language, which never made us go down the rabbit hole of whether our Higher Power was male or female. In our language, Hungarian, that would have been an absurd conversation, as third person is always gender-neutral. Ultimately, my Mother’s Father taught me everything I ever needed to know about spirituality as a child, which was: “Gratitude is the source of happiness.” What a wisely simple, yet authentic message I believed he lived every day.

I loved being around my Grandfather and I am grateful I got to spend a lot of time with him. He made me feel completely loved and accepted, precisely as I was, each day. In his eyes, I lacked nothing, had to regurgitate no poems, speak no foreign language words, or otherwise prove my knowledge and intelligence or ability. He just radiated love and joy simply because I was there. No one else in my life was this force, and I would never again experience love like his.

Getting access to my Grandfather for a visit came at a price however, because first, I had to also see my Grandmother, whom I experienced as the castle dragon. Even as a little girl, I had major apprehension around my Grandmother. When my Mother and I, and then after age eight I alone, would go visit my Grandparents, I always had to get through my Grandmother, first. Once she was done examining my appearance and shake me down for what’s new, I could finally proceed to the refuge of my Grandfather. In fact, the only time I was ever crossways with my Grandfather was when I was overtly uncooperative with my Grandmother. In my earliest memories however, I kept wondering how he could be so compliant with my Grandmother and so enthusiastically supportive of her, even when I thought she was very challenging, (emotionally) bruising and frequently, a plain-as-day, an ill-willed gossip. I never quite felt safe around her; she was in every way I experienced, lacking in the generosity of love and understanding my Grandfather represented to me. One recurring activity my Grandmother seemed to cherish was serving as the eyes and ears of her neighbors. She reported on who spoke with whom, whose marriage was ailing and who may be steppjng out with one-another. Always negative, always assuming the worst and always bonding with those similarly vested in using others for their judgement and entertainment. My Grandfather stayed clear of it all, but also said nothing. It wasn’t too far into my adulthood that I had to resign myself I would never fully understand the complexity of my Grandparent’s five-decade marriage, but I suspected their dynamic was cemented in this manner after my Grandfather returned from prison.

A few years after his death, Hungary’s post-communist government recognized the efforts of those who were instrumental in the 1956 anti-communist revolution. My Grandfather was named, and my Family members were presented with a certificate of appreciation. I watched the theatrics from afar, feeling no sense of satisfaction for what my Family endured. Human history is a complex amalgam.

One of my favorite memories with my Grandfather was his embrace of my love of his homemade potato chips. I could not get enough of his crispy potatoes; I would watch him prepare it for me from peeling them to evenly thinly slicing them into round, just-translucent pieces, then crackly-frying them until he thought I just couldn’t stand the wait. He would fish them out, season them with Vegeta, then caution me of their heat, but I’d rather burn my tongue than expectantly stare at the most loving meals of my life. He made these friend potatoes for me a hundred times, and they never got old. I am grateful, as it’s one of my go-to special events with our Family now.

One second-hand story about my Grandfather was the way he showed up for my Mother. I am not immediately thinking of how he came to wash our flat’s windows from the outside so my Mother didn’t have to….I’m thinking of how he sought my Father out one day to tell him to make sure he, my Father, took his anger out on him, my Grandfather. Apparently, that was his approach instead of stepping into the space of confronting my Father about his temper-tantrums and violence against my Mother.

I loved it when my Grandfather was at his post-retirement job, working security at a nearby furniture store. He had various shift and I wasn’t allowed with him overnight, but when the store was closed on Saturday afternoon, I had the run of the warehouse courtyard, pushing myself on the flat-dollies and other wheeled tools meant to move furniture about. I would rather spend hours watching my Grandfather at work (and make toys out of the furniture store warehouse equipment), then be stuck home alone with my Grandmother. Thankfully, the fact that I busted the skin on the back of my head open on one of those furniture dollies once requiring stitches, did not mean I was banned from the furniture store and my Grandfather’s side. I also lost some of the warehouse keys somewhere in the courtyard from time to time…but my Grandfather always made it all just fine. He loved me so; loved me precisely as I was.

Then, after age 14, I only saw him two more times. One of those times was a very dark teenage period for me. I even forgot temporarily who he was, who I had been to him, and he to me, always on my side. Instead, out of self-defense, I approached him as if he, too, was among those who saw me as irrationally angry, temperamental, and an all-around lost cause. I heavily distanced myself from him preemptively, and it wasn’t until I was in my early twenties I got around to calling him again. We had an incredibly healing conversation that day, in 1997. Every minute we spent talking on the phone made up for a year of love and compassion he was waiting to give to me, and now the transmission was complete. I felt ten feet tall that day, with a heart he had crawled into. My Grandfather, my only Family advocate, passed later that year in 1997, at the age of 77. In his last few months of life, he struggled with asbestos in his lungs, and my Grandmother was in charge of his care. What a devastating turn of events that was! She had lost her mobility due to lack of exercise years prior, and my Grandfather had been the sole grocery-shopper and errand-runner. In these last months, my Mother, during her visit, had witnessed my Grandmother handling ther food in unsafe manner, such as not refrigerating leftovers.

I felt my Grandfather’s spirit brightly one more time, and it made me feel very whole. More on that spirit-visit, later.

My Grandmother passed some years later, but I never saw her after early in 1998. I had minimal feelings about her passing; if anything, I was glad she was no longer entangled in other people’s human struggle, entertaining herself at their expense.

Leave a reply to Joy – One More Perspective Cancel reply